This Will Change the Rhythm of Your Writing Forever

Lesson 1 of "Take It from Shakespeare" with Jo Gatford

Each month, a different writing instructor takes over The Forever Workshop Substack to teach a workshop to our subscribers. Our April workshop is "Take It from Shakespeare" with Jo Gatford.

Welcome to lesson 1!

Introductions

Hi! I’m Jo — a writer, an editor, and your friendly neighbourhood Community Corner goblin here at The Forever Workshop.

I’m also a massive Shakespeare nerd, as you might have gathered by the topic of this workshop series. I’d never been that bothered about the Bard at school, but after returning to university as a mature student to finish up a long-abandoned undergrad degree, I fell in freakin’ love. Once it finally ‘clicked’ for me, it was like diving into an ocean of colour and imagery and poetry; like discovering a language I didn’t realise I could understand. And so, head-over-heels, I went on to do a Masters at the Shakespeare Institute (where I got to hang out in Shakey’s birthplace, Stratford-upon-Avon) and I’ve not really stopped reading, writing about, or teaching Shakespeare since.

As a writer, my love of Shakespeare has given me a renewed appreciation for the flexibility of language — the power of language — and how we can make and break the rules as we go…

Which is exactly what I want to do with this workshop.

I suspect a lot of us think of Shakespeare as lofty and exclusive and inaccessible, when really — once we unlock the fundamentals — we can key into many of the same linguistic approaches he used. (In fact, you’ll probably find you’re already subconsciously doing it.)

And, by taking some time to understand why and how these techniques work, it can help us to pay closer attention to the choreography of our writing, be more intentional with our word choices, and make every line sing.

In this four-part course, I’m going to encourage you to muck about with form, push boundaries, experiment with syntax, and delve into the emotion of your work to create layers of meaning.

Here’s what we’ll be looking at:

Lesson 1: The power of a line — in which we break down the fundamental rhythm of Shakespeare and bend it to our will (thanks, Will).

Lesson 2: Emphasis, rhythm and repetition — in which we borrow from Shakespearean rhetoric to create atmosphere, movement and feeling.

Lesson 3: Big feelings and vivid description — in which we find new ways of evoking emotion and imagery in our work.

Lesson 4: Take it (literally) from Shakespeare — in which we rewrite, adapt and steal shamelessly from the big ol’ beautiful bard.

Today’s lesson is free for all subscribers. Paid subs will receive full access to this and all of our workshops for $10/mo

A few final notes before we get started:

If you’re a total Shakespeare newbie, don’t panic. I’ll do my best to make the Shakespearean aspects as accessible as possible — but if you have any questions at all, please drop them in the comments.

This course was originally created for the 2024 Flash Fiction Festival, so some of the techniques and exercises are particularly well-suited to flash fiction, poetry or experimental fiction, since they tend to lean more heavily into linguistic rhetoric and non-traditional forms. However, these lessons can absolutely be applied to all forms of writing, so take what works for you and apply it to your WIP.

And above all, this is an invitation to indulge your love of language, so enjoy!

Words, Words, Words

Have I mentioned that I freakin’ love Shakespeare? ‘Cause I really do. I love the unexpected phrasing, the lyricism, the melody. I love the rhythm, the metaphor, the antithesis, the double meanings. And then there are the characters, the ridiculous plots, the witty dialogue, the pure silliness, the puns, the absolute filth. The devastating gut punches, the glimmers of hope, the humanity. The way a huge concept can be delivered in a tiny, simple little line; or a tiny, simple little concept can be expanded into a huge, unabashedly overblown display.

When I read Shakespeare, it reminds me what words can do.

When I read Shakespeare, I can feel how much he delighted in playing with language.

Take this simple little throwaway, for example:

“He words me, girls, he words me, that I should not

Be noble to myself.”— Antony & Cleopatra: Act V, Scene 2

In this scene towards the end of the play, Cleopatra has lost almost everything — her lover, her kingdom, her autonomy — and is desperately negotiating with Octavius Caesar, who is threatening to take her prisoner. Octavius tries to convince her to come quietly, promising that she will be well treated; that he has only the highest respect for her as queen of Egypt. But she knows it’s a lie; that she will be humiliated and paraded as a trophy of war if she is brought back to Rome. He leaves her to decide her fate and she laments to her waiting women:

He words me, girls, he words me.

Now, ‘words’ is not, strictly speaking, a verb. I think we can all agree on that. And yet here it works perfectly to explain how a character wields words as a weapon — to charm; to manipulate; to make Cleopatra doubt her own mind and betray her own feelings, knowing he’s lying and yet not wanting to believe the truth…

All that from a few lines of simple words, arranged in a slightly unexpected way. A noun that’s been ‘verbed’. An emphasis you can hear, clearly revealing the emotion beneath.

400+ years later and we’re still playing in similar ways:

“It’s the dead of the summer, one year after I let the preacher sing Mama into the ground and throw dust that wouldn’t settle over her grave.”

— Scorpion Season by Cressida Blake Roe (Baltimore Review)

Some careful word selection and arrangement here, too. In this case, ‘sing’ is, in fact, a verb — but it’s not usually something you do to someone. However, as it’s used here, singing someone into the ground becomes a physical, momentous action that reflects the heaviness of the emotion. The word ‘dead’, in contrast, is not attributed to the narrator’s mother, as we might expect, but to the summer. Combine this with the ‘dust that wouldn’t settle over her grave’ and we start to feel a restless, oppressive atmosphere that sets up the rest of the story.

Mini exercise #1: Action & Emotion

Take an action (anything that involves a verb of some kind):

Apologising

Pushing someone to their limit

Falling asleep

Opening a door

Worrying

Saying goodbye

Breaking something

(Or come up with your own)

Now think about the emotion behind that action. See if you can come up with an unusual way of describing it — either by turning a noun into a verb, or by twisting your verb into a strange shape to describe the event, eg:

“He words me” = he’s manipulating/charming me

“Sing Mama into the ground” = a funeral

Take a few minutes to come up with a few ideas. Use word-association to jump from image to image; thought to thought. Close your eyes and see what feelings or memories rise to the surface.

Then free-write a paragraph around your unusual little descriptive concept.

Good writing is about clever choices. And those choices often arise through play, experimentation, pushing form, and breaking rules.

So what can we learn from Shakespeare’s rule-breaking tendencies?

Well, first, we look at how he follows them.

Iambic Pentameter (de-dum, de-dum, de-dum, de-dum, de-dum)

You’ll find invisible rules beneath every kind of writing. Whether or not we know the correct grammatical term, it doesn’t really matter, so long as the words are organised in such a way to create the intended meaning or mood.

For Shakespeare, the main ‘rule’ he followed (and subsequently broke) was a form of poetic verse called iambic pentameter.

Now, I’m going to try not to get too technical here (although if you wanna delve deeper, come find me in the comments!), but essentially, iambic pentameter is a rhythm that mimics the natural phrasing of English:

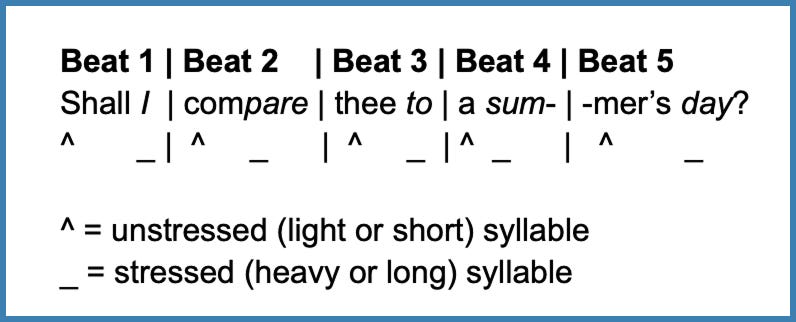

In each line there are five beats (or ‘iambic feet’)

And each beat has two syllables — one unstressed, and one stressed

This pattern creates a kind of heartbeat beneath the verse that goes:

de dum, de dum, de dum, de dum, de dum

Why? Because many English words/pairs of words are constructed in this way, with alternating stresses, eg:

proNOUNCE, suGGEST, for NOW, deLIGHT, toDAY, the MOON, preTEND, goodBYE (or even triple syllables: forGETful, comPLIance, reMEMber, uNITEd)

English speech patterns often follow this general rhythm on a sentence level, too, eg:

“Hello, good sir, and how are you today?”

“I’m going to the store to get some milk.”

“Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Say each of them aloud, count the beats and syllables, and notice which words are stressed and unstressed.

When you ‘mark up’ a Shakespearean script with this rhythm, it almost looks like a piece of music with bars and notation:

Since Shakespeare’s verse was meant to be spoken aloud on stage, it makes total sense to use such a natural rhythm of speech. But it also would be pretty boring if every single line followed the same rhythm and pattern… de dum, de dum, de dum, de dum, de dum forever would put us to sleep.

But once you understand the ‘invisible rules’ of a pattern, you can experiment with breaking them to create unexpected and impactful deviations.

Which is exactly what our boi Shakes did. Because whenever you find an irregularity in a line of iambic pentameter, it’s a big red flag that something interesting is happening.

These irregularities also serve as a form of stage direction for actors in terms of how a line might be delivered — where the emphasis falls, where to speed up, when to slow down, and what emotion is behind each phrase.

We can use these exact same techniques on the page, ‘directing’ the reader on an almost subconscious level. And, in the process, remind ourselves to pay close attention to the choice, arrangement and meaning of our words.

Here are just a few ways Shakespeare liked to mess with the rhythm of iambic pentameter:

Trochee

Instead of a beat going ‘de dum’, we swap the emphasis around so the stressed syllable comes first (dum de).

Eg:

NOW is the winter of our discontent

— Richard III

Putting such a heavy emphasis on the first syllable of a beat or phrase instantly grabs your attention. It’s a declaration. A statement. A definitive.

You can do it over and over if you really want to hammer it in:

NEVer, NEVer, NEVer, NEVer, NEVer

— King Lear

The emphasis is full of emotion here. And the rhythm and repetition drives home the hopelessness of the word ‘never’.

Spondee

This is where we have two stressed syllables within the same beat, so instead of an alternating ‘de dum’ it goes: dum dum.

Eg:

TWO HOUSEholds, both alike in dignity

In fair Verona where we lay our scene…— Romeo & Juliet

Boom boom! This is the opening line of the play, designed to snap the audience to attention. Wake up, I’m telling you a story!

To die — to sleep

NO MORE, and by a sleep to say we end

The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to.— Hamlet

The extra stresses here naturally slow the line down so that these words are delivered with extra emphasis, drawing attention to the finality of ‘no more’.

Notice how, in both these examples, the rest of the line continues on in perfectly regular iambic pentameter, rolling off the tongue smooth and easy — which only makes these irregularities stand out even more.

Teeny tiny little tweaks that make a significant difference to how a sentence sounds, feels and moves.

Shakespeare used a whole load of other irregularities to go off beat or shuffle up the rhythm — shaping the phrasing to evoke a specific meaning or feeling. We’d be here all day if I went over each of them in detail, but even a little awareness of these kinds of techniques can help you pay more attention to your writing on a line-by-line, word-by-word level.

For example:

Enjambment — in poetry, this is when a phrase is not ‘end-stopped’ but continues on into the next line, propelling the phrase forward. (In prose, the same effect could be created with a runaway/breathless sentence.)

Whether ‘tis nobler in the mind to suffer

the slings and arrows of outrageous misfortune

Caesura — a pause or switch of subject mid-line, reflecting the way our thoughts jump from one to another, connecting ideas, reaching conclusions, or contemplating contradictions in real time, eg:

To die, to sleep:

To sleep, perchance to dream — ay, there’s the rub

Monosyllables — single-syllable and simple words forcibly slow a line down and demand clarity, conjuring up a sense of truth, horror, discovery, or plain speaking. Try saying: “to be or not to be” or “lend me your ears” super fast. They want to be slow and thoughtful…

A great example of Shakespeare’s rule-breaking can be found in Macbeth’s “tomorrow” speech, which only has a handful of lines in regular iambic pentameter — the rest are disordered, dysregulated, too short, too long and out of rhythm. And there’s a very good reason for this. As the syntax breaks down, so does Macbeth’s mind, after receiving the news of his wife’s death:

Macbeth — Act V, Scene 5

She should have died hereafter

There would have been a time for such a word.

Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day

To the last syllable of recorded time,

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

Read it aloud and listen for that stuttering heartbeat. See if you can spot any of the rhythmic elements we’ve looked at so far, and think about how the arrangement of words makes you feel.

Of course, you don’t need to remember all this terminology. A lot of this can be done by ear/eye and using your writerly instincts.

But a catch-all technique I like to use is simply making note of anchor words. When you start paying attention to the rhythm and flow of a line, you’ll notice which words are naturally emphasised. Ideally, these words are the ones that will provoke the most emotion or meaning for your reader, or deliver the most important information.

Sometimes the pace and movement of a whole phrase can propel us toward one singular anchor word — carefully chosen and positioned — to elevate that sentence into a mic drop. (Look again at that Macbeth speech and see which words feel like anchors to you.)

I actually think a lot of this happens unintentionally — from the gut — in the first draft, before we think too hard about it. And then, as we edit and redraft, by recognising the shapes and melodies we’ve created, we can learn how to draw even more attention to them.

The power of a line

Alrighty, this is turning out to be a meaty first lesson, but once we’ve got these foundations laid, the world will be our oyster (a phrase coined by Shakespeare, as it happens).

I’ve thrown a lot of theory at you so far, but let’s actually see how it works in practice. And then you can have a go at identifying and borrowing some of these techniques in your own work.

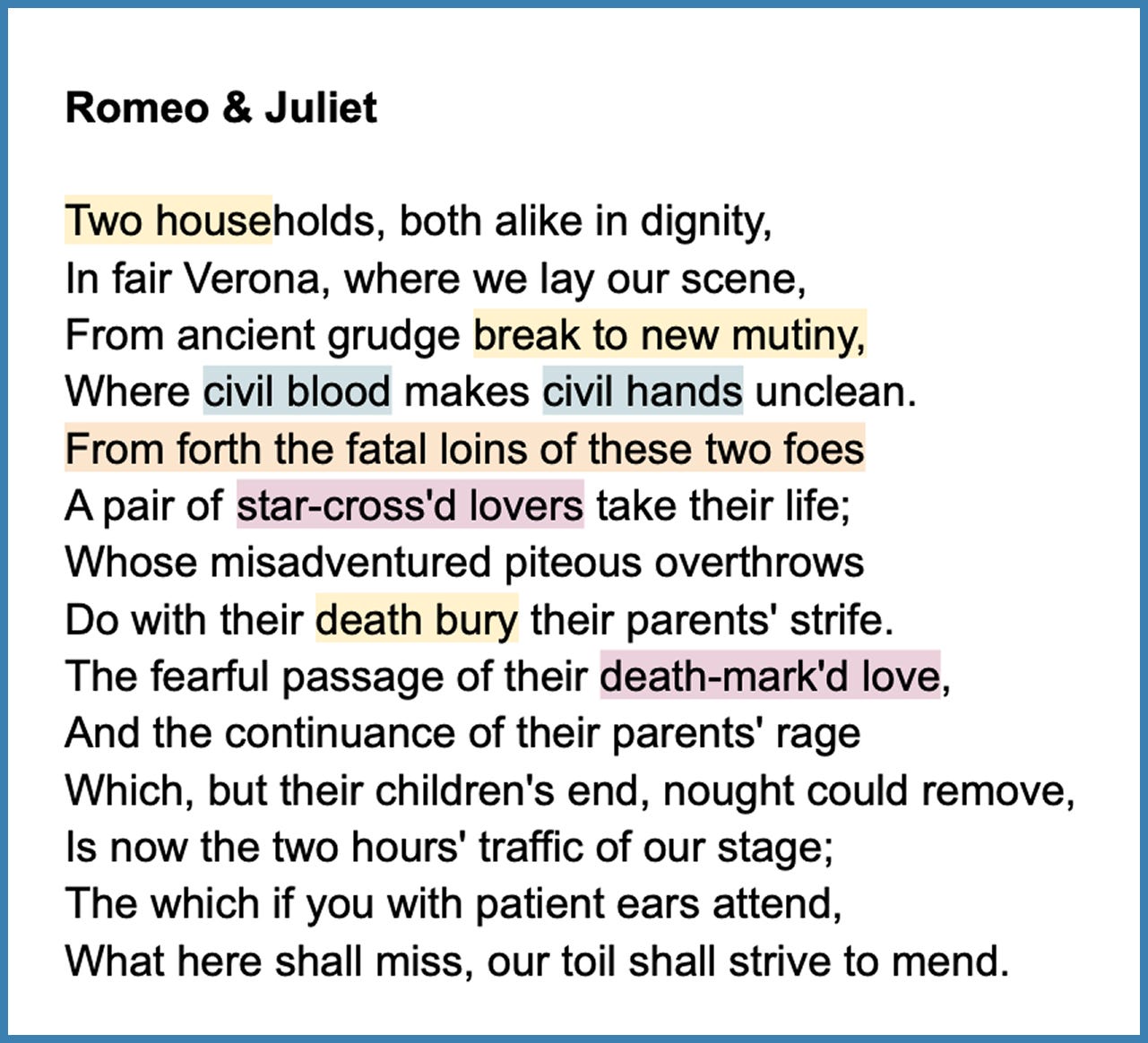

Here’s a comparison of Shakespeare and a contemporary piece of flash fiction to show how word choice and placement, pattern making and breaking can be used to craft emotive, impactful sentences.

For accessibility, because Substack doesn’t give us lots of different coloured highlighters to play with, here’s a text version:

Two households, both alike in dignity,

In fair Verona, where we lay our scene,

From ancient grudge break to new mutiny,

Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean.

From forth the fatal loins of these two foes

A pair of star-cross'd lovers take their life;

Whose misadventured piteous overthrows

Do with their death bury their parents' strife.

The fearful passage of their death-mark'd love,

And the continuance of their parents' rage

Which, but their children's end, nought could remove,

Is now the two hours' traffic of our stage;

The which if you with patient ears attend,

What here shall miss, our toil shall strive to mend.

We’ve already flagged up the spondee (two emphasised syllables) right at the start, but otherwise this opening speech remains pretty regular in its iambic pentameter. Its purpose is to deliver a necessary chunk of exposition, so most of it flows along pretty quickly and easily in that natural ‘de-dum, de-dum, de-dum, de-dum, de-dum’ rhythm. (Compare how the first line forces you to pause and emphasise certain words while the second line runs fast and smoooooth.)

There are only two other significant points where Shakespeare messes with the rhythm in this speech: in line 3 on break to new mutiny, and in line 8 on death and bury. Not only is he totally spoiling the ending of the play, but he’s flagging up the conflict and themes of the story — literally breaking the rhythm and making us pause (and consider) these emotive, impactful word choices, as well as drawing attention to the repeating B sound in break, blood, and bury. Hello, anchor words!

We also have some nice balancing phrases in civil blood on civil hands, and our poor star-cross’d lovers with their death-mark’d love — as well as some clever little antithesis by pitting dignity and mutiny against one another.

But we can go even deeper, into the very composition of each word. The first four lines are full of sharp, spitting, hissing, clipped consonants — D, T, K, S — reflecting the violence of the subject matter, before a noticeable softening as we shift into a description of the fateful lovers with alliteration (repeated consonants) of F and L sounds: from forth the fatal loins of these two foes (echoed later in lovers, life, strife, fearful). Read these lines aloud and really over-pronounce each word to hear the difference in tone.

There’s A LOT going on here. Each word, each phrase is doing an enormous amount of work for the reader/listener: setting the stage, introducing characters, creating a mood, and subconsciously wheedling those sounds and images and pacing and rhythm into our heads.

“But we don’t write in iambic pentameter any more, Jo.”

Ok, fair. But even if you strip away the verse, this shit still works wonders.

For example, read this excerpt from Shark’s Teeth and Soft Shell Crabs — a sensory banquet of a story by Maria Thomas:

“When love came, we opened wide and imbibed, imbibed. And when you my shark-toothed, ice-chipped boy, when you my surf-tumbled, sea-changed boy, when you my beach-bummed Peter Pan landed on the shore, seaweed strewn and silent, when you landed and summer ended — love survived, love survived, love survived.”

Well, looky what we have here. Many of the same techniques, albeit employed in a more prose-like way, but with all the poetry and rhetoric of Shakespeare.

Maria makes her own rhythm before playing with it, breaking it, and tossing it upon the shore. She creates internal rhyme with wide and imbibed (much like Shakespeare’s new mutiny) and a lovely balance between landed and ended to bring the lovers’ rollercoaster summer to a close.

Then we have some oceanic onomatopoeic alliteration with shore, seaweed strewn and silent, and a demand for slow emphasis on those final repetitions of love survived — leaning heavily on that first syllable (trochee) to drive it home.

Just like Romeo & Juliet, this little excerpt does a lot in a few lines — creating a vivid atmosphere and conjuring up a hell of a lot of emotion with its word choice, pattern making and melody.

Words matter. And while you don’t have to be a super-pedantic grammar nerd to make the right choices, it’s worth cultivating an ear (and a gut) for this stuff. Because whatever form (or century) you’re writing in, you’re constantly making important choices. Which word. The length of each sentence. Where to place a line break. When to reveal information or how to hide it in a metaphor.

In the next few lessons we’re going to be looking at how all those choices can help us to build structure and style, provoke emotion and deepen meaning.

But for now, I’ll leave you with one more mini exercise to keep your Shakespearean brain ticking over:

Mini exercise #2: Listen for the music in your words

Revisit your paragraph from the earlier exercise (or analyse an excerpt of your WIP) and make a note of the choices you’ve already subconsciously made:

Alliteration, assonance, repetition, balancing or contrasting words

Variety in line length, run-on sentences or fragments

Emphasis, monosyllables and irregularities in rhythm and pace

Imagery, analogy, metaphor, or unusual descriptions and word choice

Read your work aloud and listen to the melody and the beat.

How does it make you feel?

And is it doing what you hoped it would?

Share a line or two in the comments and marvel at the magic of words, words, words!

I've never given Shakespeare any thought, but do think about music when I think/feel what I am writing (rap music, country music). Sometimes, I get too abstract or indulgent, so I'll have to try and apply iambic pentameter discipline. Here are two samples from a recent essay and a WIP (memoir):

"I've spent most of my time on Earth in my head. I use my eyes and ears more than my mouth by a factor of ten. And by the grace of good sense and good genes, I've made it to the raggedy end of this mortal coil, way over here, on the far right of most graphs."

"My mother’s bed.

A bigger house. A better part of town.

We’re in the waning days of our American dream.

I gaze at her mattress, at the span of it. The sheets are barely lit. They’re all over the place, sweat upon, slept upon, kicked off by unhappy feet. I have a strong urge to curl up inside them. But I don’t. That would be weird. It’s something a teenage son wouldn’t do.

Instead, I linger at her doorway, fifteen and full of alarm."

With this second one, I wanted the word "unhappy" to serve as a bump in the rhythm of the rest, to sum up my mother at that time.

Allow me to fudge a bit and post a recently published tiny tale, only because it hits so many marks stated above.

I appreciate this lesson so much, feeling my writing has taken a turn to more joyful spirited small works

A link follows to the SORTES 21 piece « Ketchup ».

The running girl puns past fish arguing politics at a cafe. "Tuna it down," she says and runs to the circus. Her t-shirt reads I'm a pacifish. She runs the bleachers leaping over captive children watching a goat with one leg throw knives at their future. "Goat to go!" And she's off, in chase of a tuxedo cat dancing a tree of children to the river. She runs past a guard station and thuds huge pavers of off balance. The square ends blocked by a long concrete wall of division. She slows. Stops. Reads a smear of red letters. RUN