What The Hell Did You Just Write?

Lesson 1 of 12: Sorry For The Inconvenience—A Submitter's Guide to Lit Mags

Whew, OK. Lesson 1, here we go. As we get started there are a few things to know. First, I am going to try and cover everything as if someone is brand new to submitting. I don’t like that so many articles and courses take things as, “Well, duh everyone knows that!” Because when I started, I didn’t. But even for experienced submitters, I’ll have some tips & tricks along the way you might not have heard. And I’ll segment lessons to cover a range of topics. For example, you may already know everything you need to know about word counts and subgenres. Cool, skip to the part about craft vs compelling writing. If you have any questions or are confused by anything in a lesson, you can comment on this post, and I will respond. I want these lessons to be a conversation. And if you feel shy or think a question is silly, there is no pressure to ask publicly. Simply email ben@chillsubs.com, and I will answer. Quick content warning: I swear sometimes.1 I know some folks don’t like that, so just FYI.

In this lesson: I will cover identifying genres, sub genres, and length specifications before you submit. The difference between compelling writing and craft writing. You can find all of the readings and resources I share here along with a breakdown of every magazine mentioned in this lesson.

What did you write? Words, hopefully.

Mostly, you’ll be submitting poetry, fiction, or nonfiction. For each, there are two core elements you must know before submitting to any lit mag: length and subgenre.

When I started out, I had a lot of trouble determining what my subgenre was, what different types of poetry were, how long flash fiction was compared to micros, and so on.

So, let’s get into it.

Step 1: Figuring out all of this genre nonsense

Genre: There are three main genres lit mags accept: Fiction, Nonfiction, and Poetry. I think it would be condescending and a waste of everyone's time for me to explain what these three main genres are. If a magazine doesn’t accept what you’ve got, don’t submit to them. Additional genres include hybrid, interviews, art, photography, reviews, comics, audio, plays, games, and more; the specifications for those vary wildly, so always double-check guidelines.

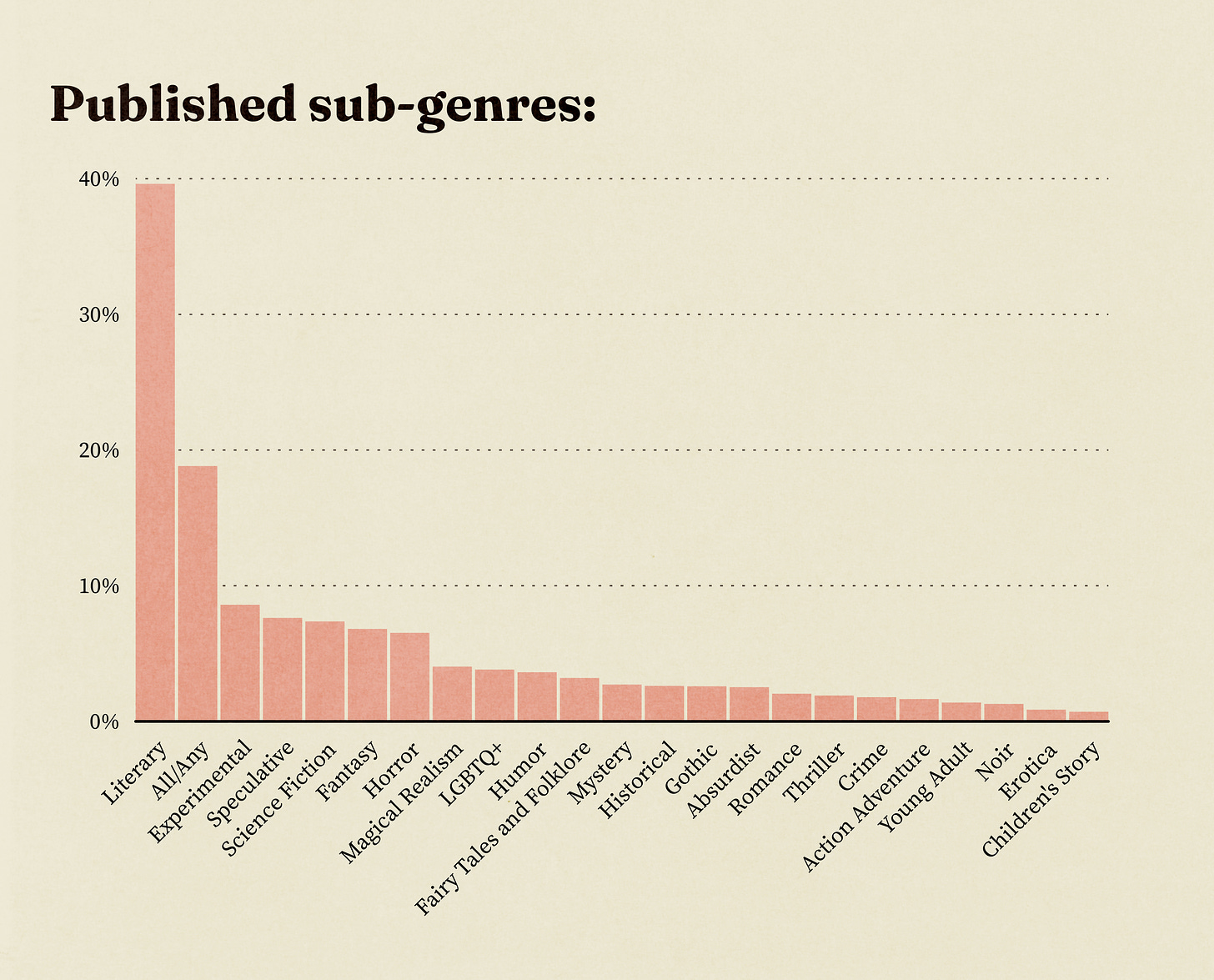

Subgenre: Welcome to the tricky part. There are over 100 subgenres for fiction, a dozen or so for nonfiction, and numerous poetry styles. If a magazine wants only literary fiction, you could be N.K. Jemisin (where my epic fantasy friends at, eh?) and still get a rejection letter, so knowing subgenre is important.

Since this is such a hassle, and since explaining every subgenre individually would take ages, I have developed three genre-identifier tools to help based on the most common subgenres.

[Fiction Subgenre Identifier] - start with the subgenre you believe your story to be, and work your way around from there.

[Nonfiction Subgenre Identifier] - fairly straightforward.

[Poetry Subgenre Identifier] - it fits or it doesn’t unless you’re an experimental poet who is good enough to mess around with strict parameters within reason.

(Someday, I’ll get Karina to code these into some handy tool for writers, but for now, I hope they help).

I have also created a list of historically prize-winning magazines for every subgenre so you can read and familiarize yourself with them. This list is not for submitting, some have shut their doors, but reading them will give you a better understanding of what each means.2

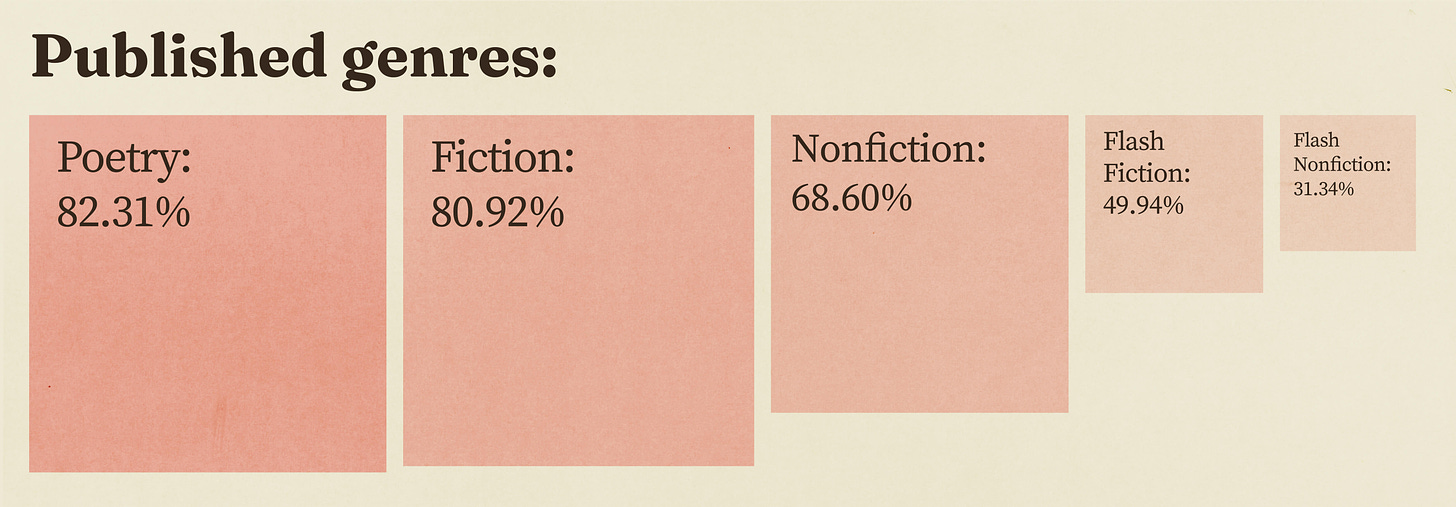

There are roughly 4,000 active literary magazines at any given moment. To give you an idea of what you’re up against, here is a statistical breakdown of what they publish:

Even with those lower percentages, you are looking at dozens of possible homes for your work. Do not waste your time submitting somewhere that doesn’t accept what you’ve written. And “literary” as a subgenre can encompass many subgenes depending on the lit mag.

Step 2: Lengths & specifications you must watch out for

Length is important because, especially for print, editors have limited space. They aren’t just being picky for the sake of it. You might not think it’s a big deal, but when I’ve interviewed editors to ask about dealbreakers on submissions, it’s one of the first things that comes up.

“To help us read and respond to all pieces in a timely manner, we ask that writers submit only one piece per reading period, and stay under 5000 words.” - Kay Allen from Corvid Queen

“Sending us work over 1000 words. We publish narratives under 1000 words excluding the title.” - Christopher Allen from SmokeLong Quarterly

“Receiving someone’s full manuscript—we’re not quite a press yet. That immediately signals to us that the author did not do their homework and might be spam submitting.” - Editors of Lucky Jefferson

“We most typically get prose submissions that are too long, packets that contain more work than we accept from individual contributors.” - Chloe from The Q & A Queer Zine

You get the idea.

This is most important for prose (fiction/nonfiction) but sometimes matters for poetry as well. But let’s start with prose.

Up to 100 words - Micro-Fiction/Drabble (Wiggle Room: Some magazines consider micro-fiction up to 300-400 words.)

500 to 1,000 words - Flash Fiction/Nonfiction (Wiggle Room: Some magazines cut off at 750 words or push the max to 1,200 words.)

1,500 to 7,500 words - Short Story (Wiggle Room: After 7500 words, a magazine will usually state their cap.)

7,500 to 20,000 words - Long Read (Wiggle Room: Sometimes called a long short story, or even a Novellette.)

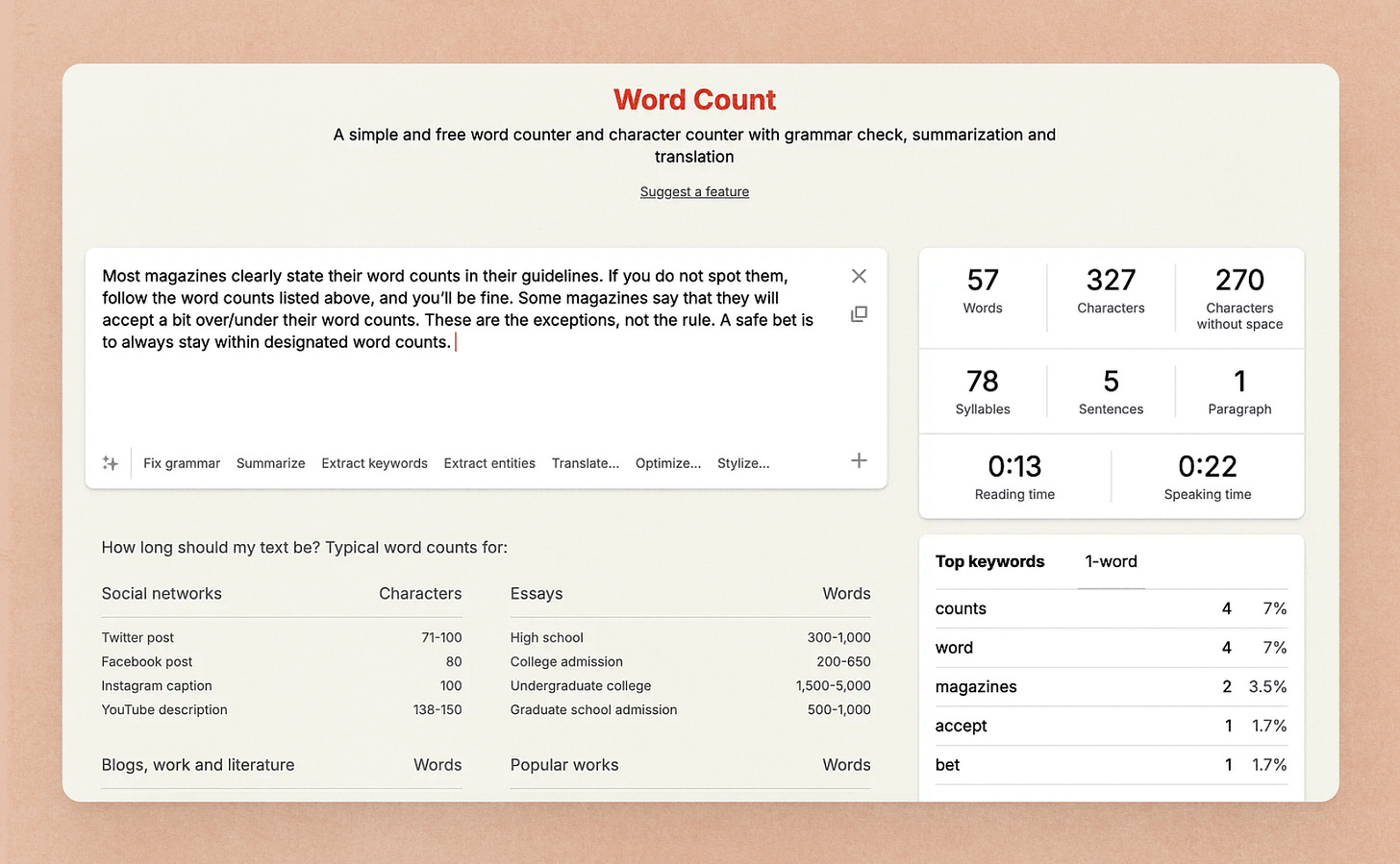

Most magazines clearly state their word counts in their guidelines. If you do not spot them, follow the word counts listed above, and you’ll be fine. Some magazines say that they will accept a bit over/under their word counts. These are the exceptions, not the rule. A safe bet is to always stay within designated word counts.

Here is a super simple, and free, word-counting tool.3

Alternatively, you can find word count listed in the bottom left-hand corner of a Microsoft Word window or by click tools → word count in the Google Docs navigation.

If you’re curious, the most common max word counts (beyond flash) are 5000 words: 22.38%, 3000 words: 12.84%, 2000 words: 8.44%, 4000 words: 7.49%, 2500 words: 6.76%, 6000 words: 5.92%, 7500 words: 5.03%, 10000 words: 4.72%, 1500 words: 4.35%, 8000 words: 3.62%

Now, for poetry.

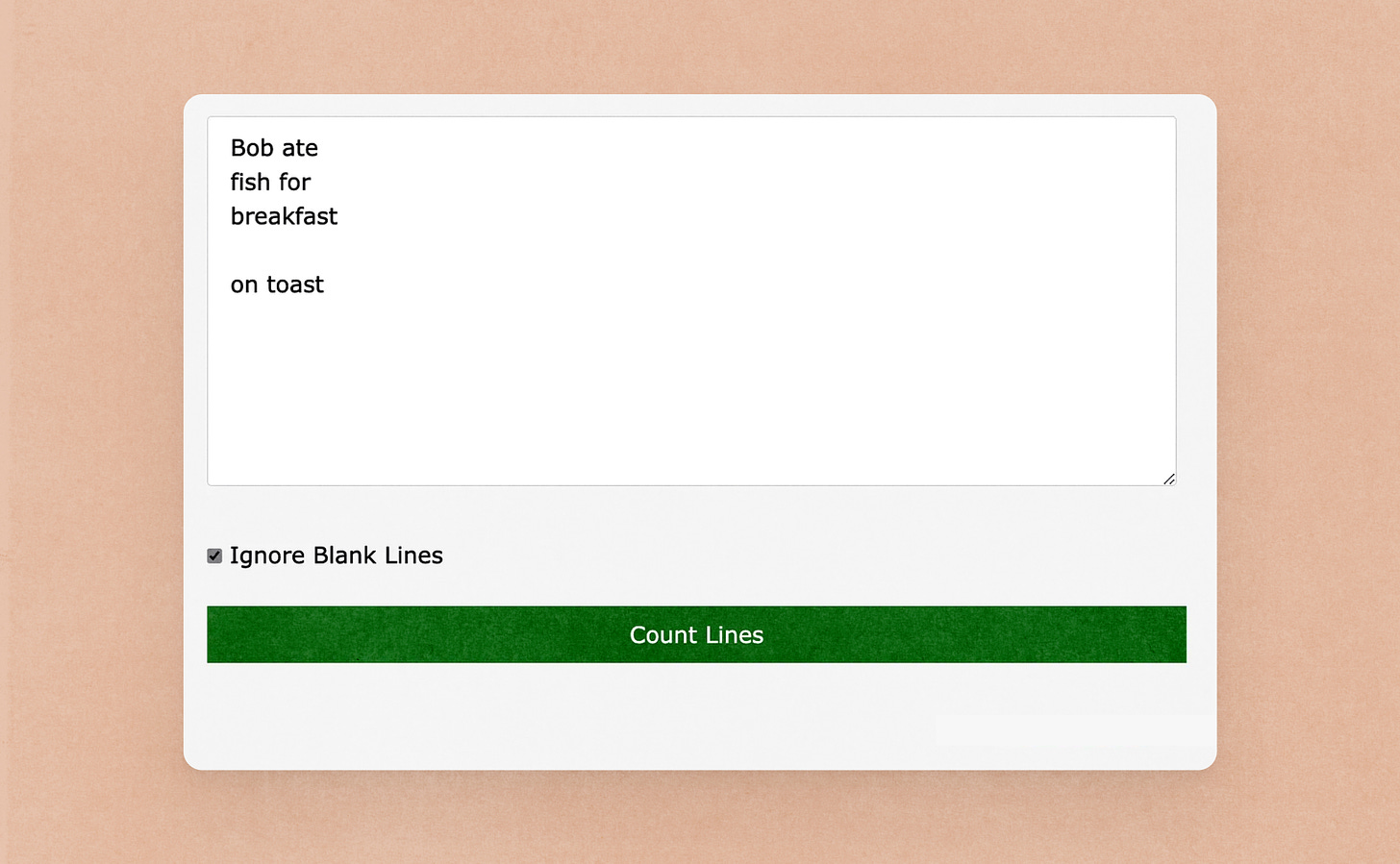

For the length of individual poems, it’s more common to see limits on page & line counts than word counts. For line counts, it’s fairly straightforward. Magazines will list them if they matter.

Here is a super quick & easy tool for counting your lines. (I like this one because it gives you the option to ignore blank lines and blank lines do not matter with line count restrictions unless otherwise stated.

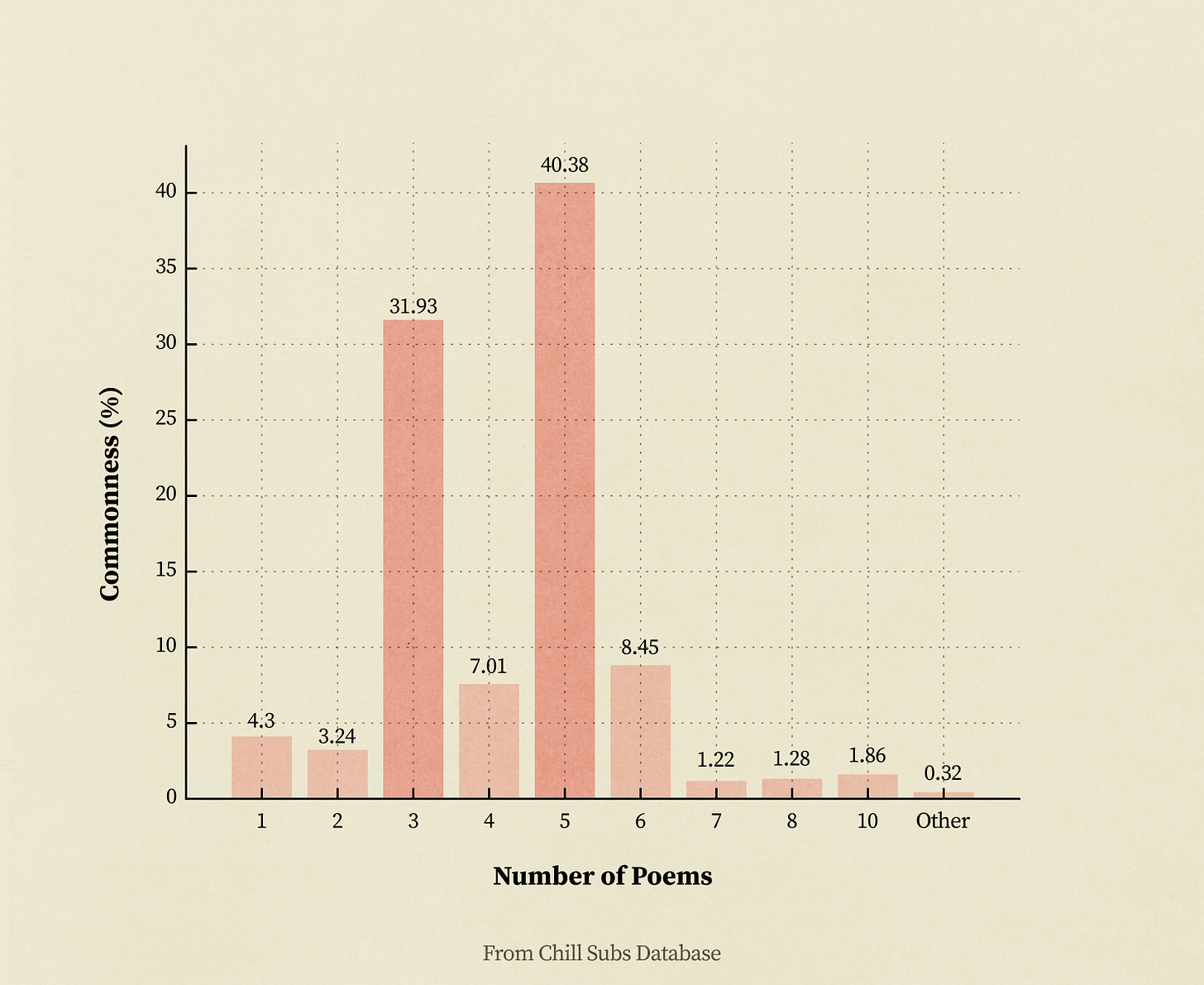

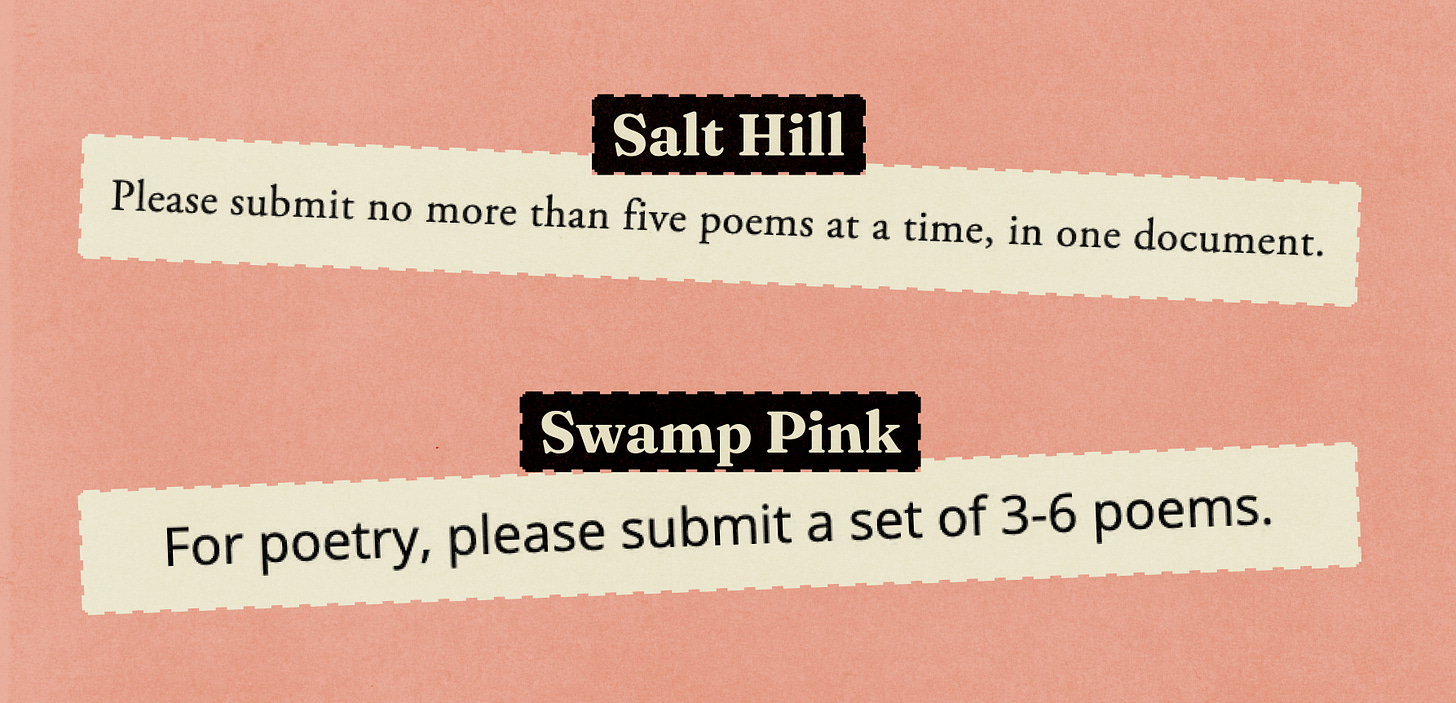

More important and common to see than line or page counts is poem counts—the number of poems you can submit at one time. The most common limits for number of poems are 3 or 5.4 It’s not even close:

Here are a couple examples of what that looks like in a lit mag’s guidelines:

Now, here is an answer to the question of craft to the best of my abilities

As a lifelong lover of boxed zinfandel and two-buck-chuck, I tend to think of craft-focused highly-prestigious lit mags as sommeliers; they want your hints of apricot, your complex notes, your oaken barrels. Is that walnut I'm tasting? Num-num-num.

This contributes to the narrative that "Literary Magazines" are only for MFA candidates. That's not the case; it is simply that several of the most prestigious lit mags were born out of MFA programs, a place that teaches the craft of writing. Craft is about technique, the mechanics of executing your piece of writing. You may have written the most compelling story ever told, and many brilliant magazines will publish it, but if you haven't nailed down the craft elements, a craft-focused magazine5 won't be interested.

This doesn't mean you can't be experimental. These days, it's not unheard of to find high-end magazines publishing stories without dialogue tags6 or poems without capital letters7. But there has to be a purpose. If I had to pin down what craft means, it is purpose; story, poem, page, line, paragraph, sentence, word. Choice matters. On the flip side, this has made some top-tier magazines somewhat of a slog which has led to a whole new generation of exceptional lit mags that care more about how compelling your work is rather than how well it is executed.

These, in my mind, are the two key factors — craft and compelling(ness?)8. You can have one without the other but need both to blow people away. Nobody knows the secret of an objectively good story or how to write an objectively good poem. It's that secret stuff only you know. I guess if I had to answer someone asking how to write something good, I'd say, fuck me down the page and leave me breathless.

I cannot teach you craft, but since the 90s, every well-known writer of literary fiction has published a book on the subject. Seriously, look at a list of the hundreds of books on writing and see how many were written before 1990. Almost none. (Then look up any list of the best writers of all time and wonder how they possibly did it!). Anyway, I’ve read loads. The best one is Reading Like a Writer by Francine Prose. Best for the nitty gritty: Dreyer’s English. Everyone has their favorites; those are mine.

So, that's the what of it. What are the technical and genre specifications of your work? What genres are you writing in? Do you focus on craft, compelling story, or both?

The one thing every fiction editor seems to agree on is that character-driven work, above all, is the best. So don't forget your character's emotional journey. That's all the concrete, probably universal advice I’ve got.

Some writers who balance craft and compelling well (in my opinion) are Kelly Link, Tao Lin, Etgar Keret, Aimee Bender, Kevin Wilson, Mariana Enriquez, Ada Limon, Leigh Chadwick, Bob Hicok, Li-Young Lee, Luke Kennard, Jenny Xie, Fran Lock, Jane Yeh

Some lit mags that balance this well: One Story, Story Magazine, SmokeLong Quarterly, Brevity, Pithead Chapel, Conjunctions, Booth, Split Lip, Rattle

Further reading:

To get a better understanding of craft writing, you have to read. Read a lot. In my opinion (keeping in mind I’m a fantasy & magical realism nerd), these are good examples to start with.

Compelling: Read How to Talk to Girls at Parties by Neil Gaiman. This is an example of fun, compelling reading without (what I’d consider) a craft focus.

Craft: Consider Scab Painting by Yoko Ogawa. Beautiful writing. Loads of depth. Hell, just read the first paragraphs of these two, and you’ll get the picture.

Feel bad about yourself: Now go and read The Game of Smash and Recovery by Kelly Link, A Friend by Kevin Wilson, or anything Mariana Enriquez writes.

BONUS: Some commonly confused subgenres with explanations by people who know better than me:

“Prose poems are poems crafted with the traditional sentences and devices of prose writing but still relying heavily on poetic devices such as heightened imagery and precision of language.

Flash fiction are stories crafted with the devices of storytelling such as story arc and tension but compressed into limited language, normally no more than 1000 words.”

Can you submit one as the other and the other as one? Absolutely. Will that get by an experienced flash or prose poem editor? Unlikely.

Science fiction vs. speculative

“…Much so-called science fiction is not about human beings and their problems, consisting instead of a fictionalized framework, peopled by cardboard figures, on which is hung an essay about the Glorious Future of Technology…

…In the speculative science fiction story accepted science and established beliefs are extrapolated to produce a new situation, a new framework for human action. As a result of this new situation, new human problems are created--and our story is about how human beings cope with those new problems. The story is not about the new situation; it is about coping with problems arising out of the new situation…”

I still fuck this up. Like, all the time.

And here is a quick & nice answer from Monica at Talk Vomit about what it means when a lit mag asks for “genre-bending” work:

For me, that’s always meant a piece that isn’t afraid to be two things at once. That might mean autofiction, or an essay with absurdist elements, or a piece of writing that isn’t quite poetry but also isn’t quite prose. I like seeing writers really push themselves because I think that helps get at emotions that are otherwise hard to explain. - Monica at Talk Vomit

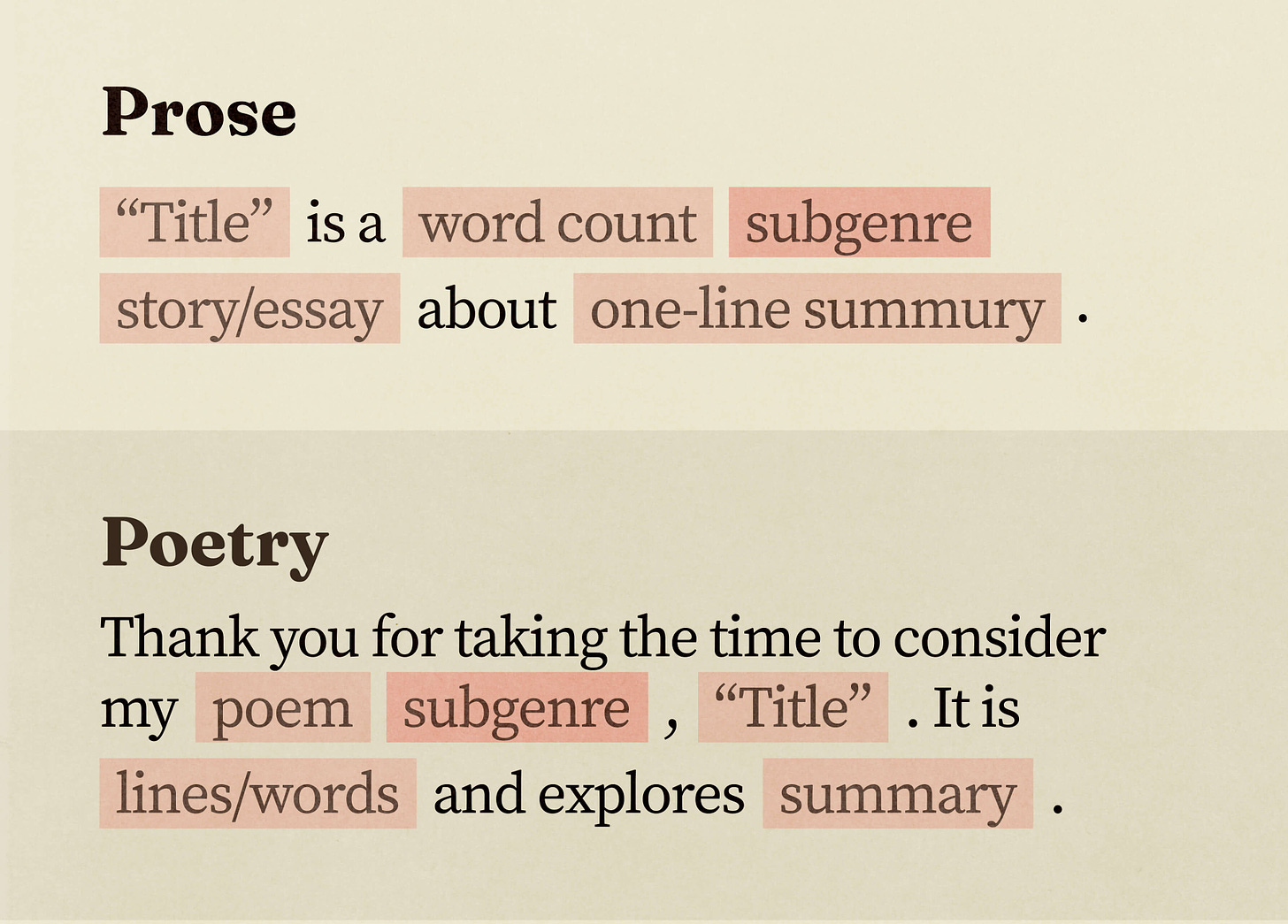

One thing that I do for each piece I write is create a blurb when it’s finished. These are what I use, but they are not any sort of “standard.” If you do this, make it your own.

Prose: [Title] is a [Word Count] [subgenre] [story/essay] about [one-line summary].9

e.g. Muppet Heads is a 600-word essay about my children.

e.g. Arf Bucket is a 3,000 word fantasy story about a dog who gets trapped in a magic well.

Poetry: Thank you for taking the time to consider my [poem/subgenre], “[Title].” It is [lines/words] and explores [summary].

e.g. Thank you for taking the time to consider my prose poem, “Wet Cats Make Friends in a Hot IKEA Bag.” It is seven lines and explores themes of motherhood and teenage angst.

This is a good habit to get into and saves me time later because I can just copy-paste these blurbs into my cover letters. One line summaries are not always necessary for cover letters, but I write a lot and sometimes I don’t remember what a story is about.

Choose 3-5 pieces of writing you have in your files. Identify all of these details and create blurbs for them. Comment the blurbs below with any questions or troubles you had along the way.

What are some other commonly mixed up subgenres you’ve encountered?

Share a piece of writing that you have found that is both compelling and expertly executed with craft.

What are your favorite books on how to write “well” and why?

This is our first lesson! How did it go for you? If you had any trouble with pacing or accessing any materials, please let me know.

VIDEO: What you can do with your what on Chill Subs:

Thank you for joining! On Wednesday, we’ll move on to Lesson 2: Why are you submitting to lit mags in the first place? If you’re new to this course, you can find the full breakdown and schedule in my introduction post.

If you enjoyed this lesson, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and sharing it with your friends.

Update: Lesson 2 is now live.

OK, fairly often.

Note on novel excerpts: so long as they can stand alone, there is no reason not to submit them as fiction. If they cannot stand alone, there are some places who accept novel excerpts specifically (and several contests).

This tool is also great for checking how often you’re repeating words in your writing.

I will discuss more about how to format these poems and bundles in lesson 6.

e.g. Guernica, Kenyon Review, The Lascaux Review, etc. (usually if a lit mag accepts only “literary works” this is a strong indicator they are craft-focused.)

I don’t want to go to the store on Tuesday because there are bears, said Sally

i love the moon / the moon loves my dad / im sad now

OMG, WHAT'S GOING TO HAPPEN NEXT! I GOTTA KNOW! PLZ, PLZ, PLZ.

Including the one-line summary is optional. I do it because I have tons of work and like that it helps remind me wtf I wrote.

good job Ben

Me again...I keep an excel spreadsheet of where I've submitted, date, date rejected, is there a fee charged for submitting and do they use Submittable.

I've also got a sheet for the stories I've got ready for submitting, genre, word count.

And another sheet for each story submitted, number of times submitted and times rejected.